-

Introduction

Among the pioneers who founded and developed the field of Public Health, several of the most significant figures were alumni or faculty of the NYU School of Medicine and Bellevue Hospital. Physicians and surgeons like William Van Buren and Stephen Smith established the connection between unsanitary conditions, such as could be found in urban areas and war fields, with the spread of disease. They advocated for public and personal sanitation and fought to establish new concepts such as patient quarantine and the development of vaccines against epidemics.

Contributions from NYU and Bellevue pioneers changed the course of medical history, from proving the clear links between unsanitary living conditions and infectious diseases, to emphasizing the importance of Public Health and the vital role it plays in the prevention of disease.

Presented by the Lillian & Clarence de la Chapelle Medical Archives

-

Understanding the Cause of Disease

With the development of the science of bacteriology at the beginning of the 20th century, breakthrough discoveries were made into the causes of highly infectious epidemics. Diseases such as yellow fever, pellagra, and tuberculosis were tackled head on by esteemed alum and faculty of NYU and Bellevue, leading to important milestones in understanding not just the cause of these diseases, but also how to prevent them.

Without the discovery of bacteria and germ theory, it would have been difficult to make the connection between the spread of disease and the importance of sanitation. Only after the underlying cause of epidemics was understood, did it become imperative to advocate for public health as a means to reduce the extensive damage epidemics brought to society.

-

Pioneering Work of Stephen Smith

Dr. Stephen Smith dedicated his life’s work to establishing public health and sanitation as one the hallmarks of the medical profession. As an advocate, he battled the housing conditions of the city’s poorest citizens living in urban tenements. Dr. Smith believed that those dedicated to the medical field best understood the public health needs of the populace, and so he strove to improve sanitary conditions all throughout New York City.

Working with the Council on Hygiene and Public Health, Dr. Smith undertook a survey of city health conditions in 1865, resulting in a report known as the Magna Carta of municipal sanitation in the United States. This work led to the establishment of the Department of Health in 1866. Dr. Smith was also a founder and first president of the American Public Health Association.

As a surgeon and professor, Dr. Smith’s major contributions include being a principal figure in the forming of the medical school at Bellevue Hospital; authoring several texts, including his surgical manual Handbook of Surgical Operations, widely used during the Civil War; documenting the emergence of sanitation and public health in New York in his book The City that Was, written when he was 90 years old.

-

The United States Sanitary Commission

Dr. William Holmes Van Buren, a surgeon and teacher at the NYU Medical Department, was a key figure in the United States Sanitary Commission, a civilian organization that provided much needed support to sick and wounded soldiers and their families during the American Civil War. Through the Commission’s efforts, money was raised to provide donations of much needed supplies to soldiers on the battlefield, in addition to providing volunteer nurses and doctors to aid with medical relief efforts. Dr. Van Buren’s contributions include the 1861 publishing of a series of monographs for Army surgeons, including his own Rules for Preserving the Health of the Soldier, which set standards of care for surgeons on the battlefield.

Dr. Van Buren would remain keenly interested in public health after the war, serving as the founding member of New York City’s Council of Hygiene and Public Health.

-

Controlling Tuberculosis

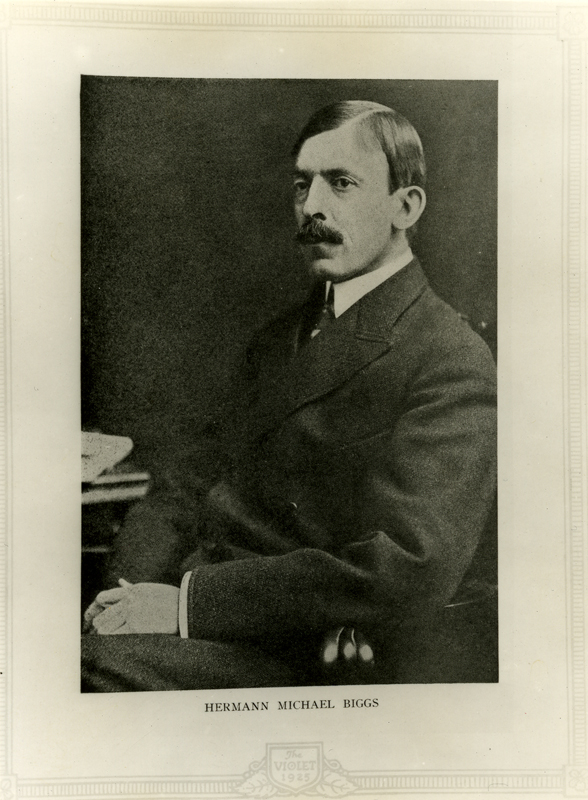

Dr. Herman M. Biggs, a bacteriology pioneer in the United States, developed methods for the prevention and containment of the highly infectious disease tuberculosis, the leading cause of death in the 1880’s. As a professor of pathological anatomy at Bellevue Hospital Medical College, Dr. Biggs issued a widely distributed pamphlet on the prevention of tuberculosis in 1887, and ensured the disease’s classification as reportable in 1897. The spread of prevention information, along with the close tracking of tuberculosis outbreaks, facilitated treatment and containment of this disease, and served as a model for public health officials.

-

Typhoid in the Battlefields

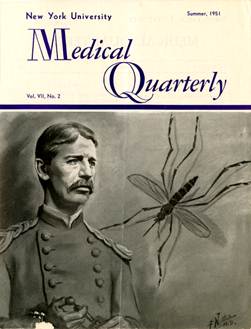

An 1873 graduate of Bellevue Hospital and Medical College, Dr. Walter Reed enlisted in the U.S. Army Medical Corps in 1875. Early in his career, he conducted research that led to the diagnosis of diphtheria in the battlefields. In 1898 he was appointed by Surgeon General George M. Sternberg to lead the Typhoid Board, with the charge to investigate the epidemic of typhoid fever that swept military camps. Dr. Reed and his staff confirmed that the disease ravaging the camps was indeed typhoid, spread by flies and unsanitary conditions at the camp. Understanding how typhoid was communicated allowed military officials to establish sanitary guidelines in all military camps, containing the spread of this disease in the battlefields and saving many lives.

Fighting Yellow Fever

Dr. Walter Reed was appointed to the Yellow Fever Board in 1900, taking him away from his work on typhus. He became part of a quartet of doctors who would attempt to understand the cause and contagion of the tropical disease yellow fever. Dr. Reed traveled to Cuba, where the Board worked tirelessly on controlled experiments, concluding that yellow fever is transmitted by the mosquito Aedes aegypti. This discovery disproved the widely held belief that the disease was caused by human contact with soiled bedding and spread through body fluids.

With a clear understanding of how yellow fever is spread, the next step was to develop a way to contain the disease. Dr. William C. Gorgas built on the work of Dr. Reed, and instituted measures for the control of mosquito populations, which effectively managed yellow fever epidemics.

-

Typhoid in the City

Dr. Sara Josephine Baker, a lecturer and graduate of the University and Bellevue Medical College, was a pioneer in the early methods of public health management. As Assistant Commissioner of Health for the New York City Department of Health, she led efforts to identify and quarantine “Typhoid Mary,” an asymptomatic typhoid carrier who was the source of a deadly outbreak in 1907. This was the first known case of a healthy person who was a carrier for a deadly bacterial disease. Understanding that healthy people could carry and spread typhoid furthered research and knowledge into the transmission of other infectious diseases.

Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

-

Focus on Children's Health

Dr. Baker continued her efforts on behalf of public health as an advocate for the sanitation of milk and the welfare of children in the city. As director of the Bureau of Child Hygiene, she developed the use of milk stations, where pasteurized milk was provided to families as an alternative to the often tainted milk commercially sold. In addition to pasteurized milk, she introduced the use of infant formula. Thanks for her innovations, mortality rates for children dropped more than 40 percent between the years 1908 and 1914. Dr. Baker’s efforts to secure the public health of children led to the establishment of the United States Children’s Bureau in 1912, bringing her successful local approach to the entire nation.

-

The Origins of Pellagra

Dr. Joseph Goldberger, an 1895 graduate of the Bellevue Hospital Medical College, discovered the cause of pellagra, a widespread devastating disease whose symptoms included severe dermatitis and dementia. Pellagra caused devastating fatalities concentrated in the southern United States in 1918.

Dr. Goldberger proved that pellagra was not caused by an infectious agent, as was believed at the time, but rather by a simple dietary deficiency that, if addressed, could not only cure but also prevent pellagra epidemics from occurring in the first place. For his work on the etiology of pellagra, Dr. Goldberger was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1929.

-

Developing the Polio Vaccine

The NYU School of Medicine is esteemed in having two prominent alumni who were key figures in the development of both the IPV and the OPV vaccinations for the prevention of the communicable disease known as polio. A disease that is spread through human-to-human contact, and usually enters the body via contaminated water or food, the polio virus is extremely infectious. It causes paralysis, and disproportionately affects children between the ages of three to five.

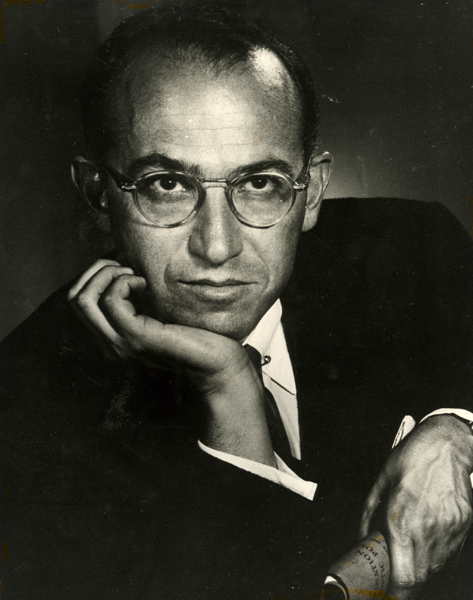

In 1947, Dr. Jonas Salk, a 1939 graduate of the NYU School of Medicine, committed himself to developing a vaccine against polio. Working at the University of Pittsburgh, with support from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now the March of Dimes), Dr. Salk and his team advanced work done by previous researchers. In 1954, he conducted a large field trial of inoculations. Positive evaluation results from this trial cleared the way for injected vaccinations (IPV) given nationwide for the prevention of polio.

-

Progress & the Polio Vaccine Today

In 1957, Dr. Albert Sabin, a 1931 graduate of the NYU School of Medicine, introduced the oral polio vaccine created from a weakened live virus. The oral vaccine managed to successfully prevent the initial intestinal infection caused by polio, thereby preventing further transmission of the disease. Dr. Sabin’s OPV vaccine, a more cost-effective and deployable improvement to the Salk injection vaccine, was licensed in the U.S. in 1961.

In 2000 the ACIP (Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices) recommended returning to exclusive use of an IPV vaccine in the United States, to eliminate the instances of polio that could be potentially acquired from the OPV vaccine. As a result, the United States no longer administers the OPV vaccine, though it continues to remain in use throughout the world.